In recent weeks DANSRD has received a number of questions from both students and faculty regarding ANCSA Settlement Trusts. Most of these questions seem to have been generated by a recent push by some of the ANCSA Regional Corporations (ANCs) to establish these Trusts in response to changes in tax requirements under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, also known as Public Law 115-97. Others have come because these Trusts were part of required course work. While we recommend that shareholders ask their respective ANCs for information if a Settlement Trust is being considered, some questions had come from students who simply were not understanding the information the ANC had provided. With that in mind, we put together some basic information to try to answer some of the questions.

First, the Settlement Trust option for ANCSA Corporations (ANCs) is not new. There were 18 established by December 31st 1999[1] and over 30 are now in existence.[2] The tax incentives are new and they are substantial for the ANCs so in 2018 there is renewed interest in establishing these Trusts. Settlement Trusts were included in the statute[3] as part of the “1991 Amendments’ and there is some good information about the original intent of the Trusts in the “1991: Making it Work’ publication published by the Alaska Federation of Natives to explain changes to ANCSA made in 1987. That publication, which was re-issued by Sealaska in 2001, describes Settlement Trusts as follows:

“Under the “1991’ law, a Native corporation may transfer some or all of its assets – such as surface land, stock and property – to a trust created just for the benefit of its shareholders. The main purposes of the Settlement Trust are to promote the health, education and welfare of Native shareholders; preserve Native heritage and culture; and give greater protection to Native corporation lands.’[4]

In general, the Settlement Trust option appears to be a good one for ANCSA Corporations. It is one that has long been under-utilized for various reasons involving tax structure. Those who want to learn more about this, and the tax law changes, should review a very recent article by Bruce Edwards entitled “The 2017 Tax Act and Settlement Trusts’.[5] The new tax law allows Settlement Trusts to be funded on a pre-tax rather than an after tax basis, as has been the case since 1988, so this is a good incentive for the Corporations as it will give them a substantial tax-break.

These trusts are intended to “promote the health, education and welfare of the beneficiaries of the Trust and preserve the heritage and culture of Alaska Natives‘ and should be able to provide some benefits for shareholders who will then be referred to as beneficiaries of the Trust, however it is important to understand how they work so that people do not have unrealistic expectations.

You can examine a few different Trust Agreements online to get an idea what they contain. The Bristol Bay Native Corporation Trust Agreement online at https://www.bbnc.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Trust-Agreement-of-the-BBNC-Settlement-Trust.pdf is one of the longer Agreements. If you look at paragraph 6.1.1 Types of Benefits, you will get an idea of what BBNC envisions their Trust might do for beneficiaries. It is important to understand that these benefits are things that could be provided by the Trust, but there is no guarantee that they actually will be. The ability of the Trust to provide any or all of these benefits is dependent on the amount of assets contributed to the Trust and how well those assets are managed going into the future. It is up to the Trustees to decide how best to manage the Trust and distribute benefits.

Settlement Trust Agreements vary. They all will contain some boiler plate language that indicates their compliance with the law, but beyond that shareholders being asked to vote on establishing a Settlement Trust need to read the Trust Agreement for their own ANC and be sure they understand its contents. Something important to consider is who the Trustees will be and how they will be chosen. The Trustees will have very significant power over the assets in the Trust and hold the responsibility for its success so it is important for them to know what they are doing. Some of the Settlement Trust Agreements call for Trustees and ANC Boards of Directors to be one and the same, but the duties and responsibilities for these two positions are quite different, so meeting them both could be quite challenging.

How does a Settlement Trust work?

When the Corporation establishes a Trust it is giving some of its assets to the Trust and the Trust will then manage the assets separately from those that the Corporation keeps. The ANC can do this in one of two ways: on a regular basis, perhaps annually, or as an endowment which means the Corporation makes a large one time contribution to the Trust. Corporations that are using the Settlement Trust as a vehicle to reduce their tax burden would likely make annual contributions. If an ANC endows a Trust this does not prevent it from making more contributions later on.

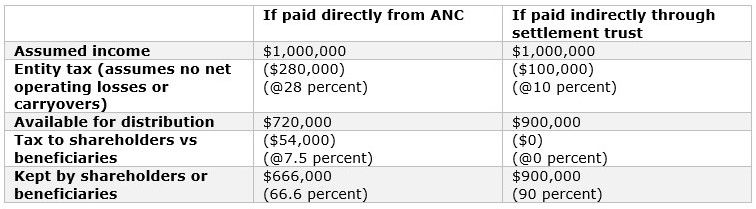

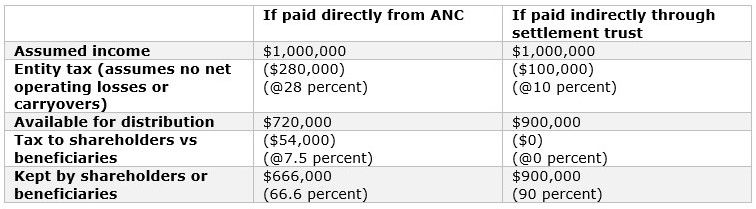

Under the new tax law, the Corporation makes those contributions to the Trust pre-tax, and then the Trust pays tax at a lower rate. If the Corporation pays dividends to shareholders those dividends are subject to taxation. If the Trust pays distributions to beneficiaries, those distributions are, in most cases, tax exempt. Distributing the assets through the Trust means, at least in theory, that more money is available to the beneficiaries. The CIRI website provides a table which describes clearly how much money might be saved by using a Settlement Trust. It shows what recipients actually keep from $1 million in corporate earnings distributed by an ANC versus a Trust:

Table credit: https://www.ciri.com/overview-of-settlement-trust-after-2017-tax-act/

While there is a clear tax benefit, it may be difficult for a Settlement Trust to actually serve to “promote the health, education and welfare of the beneficiaries of the Trust and preserve the heritage and culture of Alaska Natives’ over the short term in ways that the Corporation does not already do, unless it is very well funded. In order for the principal or “corpus’ of the Trust to grow it will need ongoing contributions from the ANC plus income from investments to remain in the Trust so that over time it can make larger distributions. The Trust cannot pay out everything it receives from the ANC every year because if it does the principal will not grow. If the ANC experiences some bad years where profits are low or non-existent, it may not make any contribution to the Trust. If that happens the Trust needs to have enough in its principal to hold its own using investment income until contributions start again.

If the only actual benefits to Trust beneficiaries are tax free distribution payments, occasional educational benefits, elders benefits and assistance with funeral potlatches, then these benefits are the same as what most shareholders currently receive with the exception of tax exempt distributions. If distributions from the Trust are always made in the form of cash to beneficiaries, rather than used for some of the things the BBNC Settlement Trust envisions, then it is up to those beneficiaries how the money is spent. That money may or may not be spent to “promote the health, education and welfare of the beneficiaries of the Trust and preserve the heritage and culture of Alaska Natives’. A less obvious but longer term benefit to beneficiaries is the protection that assets acquire once they are a part of the Trust and can no longer be used by the ANC in ways that may incur risk. This does not mean that there is no risk involved with the kinds of investments a Trust can make but risk will be much lower as long as the Trust is managed responsibly.

The tax exemption will result in some small savings for most shareholders who would otherwise pay taxes on an ANC dividend. Shareholders with higher incomes may see more savings. It will make no difference for those whose incomes are so low that they already pay no federal income taxes. The tax exemptions correspond to different tiers described in the new tax law so most of the time they will apply. If a much larger than usual distribution were to be made then it most likely would not be tax exempt because it would fall into the Tier 4 category of distributions.[6]

How much these Trusts can provide to beneficiaries is really dependent on two things: the amount of the assets that the Corporation contributes to the Trust, and how well those assets are managed going into the future. A Trust cannot do more than it has money for. The BBNC Trust Agreement provides a very expansive picture of all the things it might do. Other Trust Agreements are a lot more conservative in their description of distributions than the BBNC Agreement, and may provide a more realistic picture of what a Settlement Trust could provide.

There is a possibility that Settlement Trusts could do a lot more for Alaska Native communities than the ANCs are currently able to but, as noted earlier, their success will be dependent on how well they are funded by the ANCs and the skill of the Trustees who are managing them.

What will NOT happen if a Settlement Trust is established?

- Land placed into a Settlement Trust will not become Indian Country.

- A Settlement Trust cannot operate a businesses and cannot “go under’ as a result of a joint venture the ANC is involved in failing.

- An ANC cannot convey sub-surface land to a Settlement Trust.

- Trust distributions are unlikely to be a whole lot more than dividend payments were at least until such time as the Trust is well established and its investments are doing well.

- If land is placed into the Settlement Trust it cannot then be conveyed to another party.

- Shareholders will not vote on the transfer of assets from the ANC to the Trust UNLESS the ANC is going to transfer all or substantially all of its assets.

- The ANC cannot take back assets after it has contributed them.

What should shareholders ask about?

Each ANC has provided different information for shareholders regarding these trusts. We looked at several FAQ sheets and found Calista Corporation to have the most transparent and comprehensive document. We mentioned earlier that shareholders should review materials from their own ANC however most of what Calista has is very standard information and you can review this at https://www.calistacorp.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Settlement-Trust-FAQs-FINAL.pdf

After researching all of the available materials we compiled a list of general questions that we felt were important, especially for shareholders. Some of these are questions we had been asked by students, and we found we could not answer them using the materials available to us, so it is likely that others would also have trouble answering them:

- Under what circumstances would distributions from the Settlement Trust received by beneficiaries NOT be exempt from taxation?

- What is the real impact for people in different tax brackets?

- How will distributions from this trust affect federal needs-based eligibility programs such as food stamps? (This may be covered under 43 U.S.C. § 1626(c)(E) https://lbblawyers.com/ancsa/1626.htm but it would be a good thing to verify)

- If Trustees are going to be the same people as the ANC Board how will the rights and responsibilities of each position differ?

- Could the dual responsibility of being a Board Member and a Trustee create a conflict of interest and, if so, how would that be addressed?

- What assets are going to be placed into the Trust?

- Will the distribution that I receive as a Trust beneficiary be INSTEAD OF or IN ADDITION TO the dividend I usually receive from my ANC?

- Will any surface land owned by the ANC be placed into the trust?

- For how long and how often will the ANC continue to contribute to the Trust?

- Is there any requirement for the ANC to continue making contributions to the Trust?

- Suppose the ANC has no need for a tax deduction in a given year, will it still contribute to the Trust?

- How will this Trust affect shareholder’s future rights and responsibilities with their ANC? (Some ANCs already have problems getting enough shareholders to vote; will this change make things worse?)

- Will Trustees invite shareholder input on decisions on the addition of additional types of distributions that could be created in the future and, if not, how will the Trustees make those decisions?

- If my ANC has a Foundation how will this be affected by the Trust?

- What happens to the Trust if shareholders vote to lift restrictions on Corporation shares?

In Conclusion:

Settlement Trusts can secure investments in ways that the ANCs do not, and have the potential to provide significant benefits to shareholders but these benefits will be dependent on:

- The terms of the Trust Agreement.

- The amount that the ANC contributes to the Trust.

- The skill of the Trustees.

DANSRD cannot advise you on how to vote but we recommend you educate yourself thoroughly if you are being asked to vote on establishing a Trust. If you have already voted, be an active beneficiary and keep abreast with your Trust and what it is doing!

[1] Edwards, Bruce N. UNDERSTANDING AND MAKING THE NEW SECTION 646 ELECTION FOR ALASKA NATIVE SETTLEMENT TRUSTS. Alaska Law Review 2001. Page 223

[2] QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ABOUT THE DOYON SETTLEMENT TRUST. FAQS

[3] 43 U.S.C. § 1629e Settlement Trust option https://lbblawyers.com/ancsa/1629e.htm

[4] 1991: Making It Work A Guide to Public Law 100-241 1987 Amendments to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. Alaska Federation of Natives Reissued in PDF October 2001 by Sealaska Corporation www.sealaska.com. Page 43

[5] Edwards, Bruce N. THE 2017 TAX ACT AND SETTLEMENT TRUSTS. ALASKA LAW REVIEW Vol. 35:1 https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1538&context=alr

[6] Edwards, Bruce N. THE 2017 TAX ACT AND SETTLEMENT TRUSTS. ALASKA LAW REVIEW Vol. 35:1. Page 25, 26