We often forget just how unique the Department of Alaska Native Studies and Rural Development (DANSRD) is in the world of Indigenous higher education and how fortunate we are to have programs that emphasize Alaska Native and rural student needs and perspectives as learners, researchers, and development practitioners instead of objects of study or top down planning. Last year I started looking closely at our graduates’ senior and master’s projects and theses to understand what areas DANSRD students are most interested in and why, and with the budget crisis this summer I began also gathering information about the impacts of DANSRD graduates in their communities. So, this fall when I saw the call for papers for the Northern Political Economy Symposium in Rovaniemi, Finland I decided to put some of the work I’d been doing together and submit an abstract.

I spent a week in Finland in mid-November, first in Helsinki and then on to Rovaniemi to present at the Northern Political Economy Symposium at the University of Lapland. In Helsinki Saami linguist Irja Seurujärvi-Kari, my excellent host, introduced me to her friends and colleagues, including Hanna Guttorm and Pirjo Virtanen, at the University of Helsinki Indigenous Studies program and we spent a lovely two days visiting and talking about Indigenous issues in Finland. I was able to speak to Professor Virtanen’s Introduction to Indigenous Research Methods class about my teaching and research at UAF and listen to some of their collaborative discussion presentations of different Indigenous research methods from around the world (if I can figure out a way to copy that assignment in a mixed face-to-face and distance class I will, so students be prepared!). I also attended their lecture series on “Sacred Spaces” – starting with presentations on sacred trees in the Amazon and in Estonia.

Then it was off to Rovaniemi for the Symposium. The Symposium theme asked, “What is left of development in the Arctic?’ and called for topics related to the potential (or lack of potential) for sustainable development in the Arctic. My paper, “Development Dilemmas: Rural Development Students Imagining a Sustainable Future in Alaska,” looked at the projects and theses produced by University of Alaska Fairbanks Rural Development Master of Arts students as a reflection of changing attitudes towards development in rural Alaska. Our students’ work illustrates how the program has helped increase Alaska Native and rural peoples’ ability to participate in dialogues and negotiations about development in rural Alaska, brought Alaska Native perspectives into these development dialogues, and helped students generate self-defined visions of what development means. I think more than anything, attendees at the Symposium were impressed to hear about educational programs focused on Indigenous needs and perspectives and whose graduates (for the MA) are 65% Alaska Native.

The trip reminded me of how special our programs are, but it also reminded me that DANSRD faculty and students have not been very active in sharing and communicating our scholarship with people outside of Alaska and our immediate community and we do not pay enough attention to some of the ideas being developed in other parts of the world. Here are just a few of the interesting people, publications, and ideas from my trip.

- Irja Seurujärvi-Kari, Pirjo Virtanen, Hanna Guttorm, and their colleagues have a new book on Indigenous research methodologies coming out next year, but in the meantime their Encyclopaedia of Saami Culture is a great resource for learning about Saami people.

- Symposium keynote speaker Reetta Toivanen of the University of Helsinki discussed the concept of “Arcticism’ (modeled after Said’s “Orientalism’ – the way in which various discourses inform Western perceptions of the Arctic) in her presentation entitled “Whose development are we talking about? European fantasies on the Arctic.’ The term was originally coined in Arctic Discourses (2010), available at Rasmussen Library.

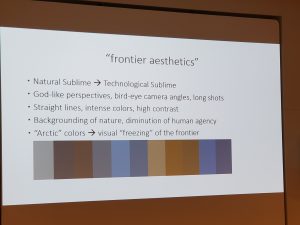

- As many of my students know, I love visual analysis and am still waiting/hoping for a student to do a visual analysis project. The Arctic Institute’s Liubov Timonina’s “Imaging and narrating development in the Arctic: Visual storytelling in times of Capitalocene’ looked at the way images shape conceptions and marketing of oil and gas development in the Yamal Peninsula. Google “Yamal’ and see if you can see the “frontier aesthetic’ she describes. How do these images compare to the images you get when you search for “Prudhoe Bay’?

- Gerard Duhaime of Université Laval looked at how public policies reproduce or amplify inequalities in his presentation “Market inequalities and the reproduction of unsustainability in Nunavik.’ It made me think about the ways our laws around subsistence also reproduce unsustainability in rural communities. I’m also going to check out Arctic Food Security (2008), edited by Duhaime and Nick Bernard, also available at the Rasmussen Library.

- We often talk about Canada in my classes on the circumpolar north, but it can be hard to grasp the variability in the Indigenous settlements across the country and how they have responded to colonialism. Philippe Boucher of Concordia University focused on understanding Inuit voices and leadership in “Sustainable development through the Inuit cooperative movement.’

- In his presentation “’North Plan’ — What’s left for Northern Indigenous communities? Can the North bring its riches back?’ Mathieu Boivin, University of Montreal, looked at how Quebec’s “Plan Nord’ prioritized non-Indigenous peoples in planning and development and its impacts on Indigenous peoples. I enjoyed speaking to Philippe and Mathieu about the Indigenous response to colonialism and Indigenous educational opportunities in Canada.

- Susanna Pirnes, University of Lapland, presented on “History as a resource in Russian Arctic politics,’ looking at the use of historical imagery to establish Arctic identity. The presentation is from her chapter in Resources, Social, and Cultural Sustainability in the North (2019). The book was edited by Symposium organizer Monica Tennberg, Hanna Lempenin, and Susanna Pirnes, all of the University of Lapland and includes chapters from several presenters at the Symposium.

- I had a great time talking to Frank Sejersen, of the University of Copenhagen about development and Indigenous approaches and perspectives. His article “Brokers of hope: Extractive industries and the dynamics of future-making in post-colonial Greenland‘ (2019) looks at how mineral extraction relates to ideas of national independence and is available online to UAF students if you sign in through the Rasmussen Library.