If you are an Alaska resident you probably just got your Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD). The State of Alaska paid out $1600 to every qualified Alaskan during October. The money is “free money’, the only thing we have to do to get it is fill out a short form, and we can spend it any way we like. It is free for the State too … all they have to do is go out to the money tree and pluck the amount they need to pay for the PFDs … Well, maybe not.

OK, now I got your attention so let’s talk about money a little more carefully. How well is that money behaving? What part does it really play in our lives and who is in control? Do we control money or does it control us? Where does the money come from and how does it affect our ability to adhere to Native values that we have been taught have their roots in “cashless’ societies … values that teach us to share with and care for others?

Whose values you ask? Good question, because there is no one universal set of Native values and by no stretch of the imagination do all Native people adhere to the same values today. For the purpose of this article I used the ones I myself live by which have their closest cousins in the Athabascan Values agreed upon at the 1985 Denakkanaaga Elders Conference (https://www.ankn.uaf.edu/ancr/values/athabascan.html). You can find other sets of values for different Alaska Native groups and all are pretty similar in terms of reminding us to share, work hard, show responsibility to our communities, and respect and care for elders and children. All of them stress respect for the land and for Native traditions and urge us to be honest in all that we do. None of them talk directly about money so now we will take a look at where money fits into those value systems.

Money has been around in one form or another for a very long time although it has been utilized differently by various groups. Before money in the form of cash came along, societies had different items of value that they used in the process of trade. While cash as we know it now (coins, paper money etc.) may be relatively new in some Indigenous communities, trade has been around for a long time. Can we say that we are practicing Native traditions when we use money? Perhaps not, but how we use it certainly can (and should) connect back to those traditions and values. The money itself is nothing more than a medium of exchange, a tool that we can use wisely or unwisely as we choose. Wise use of resources seems to be a pretty universal Native value.

The question we might ask ourselves is this: “How do we take a tool which has been used by some for a long time to support systems which perpetuate inequality and unfairness, and instead use that same tool within our own systems to do the opposite; insure equality and fair treatment for everyone?’

Indigenous Peoples did not participate haphazardly in trade. They placed a value on different items and expected certain amounts of other items in return when they traded with each other or with neighboring tribes. When they began trading with colonists and long distance partners the trading networks expanded and over time began to include cash in some of the transactions. The more expansive the trade network became, the more likely you were to see money involved, until we reached the point we are at today where the large majority of business transactions in North America involve some exchange of cash. Responsible involvement in the trade network certainly met the Athabascan values of self-sufficiency, hard work, and care and provision for family and can continue to do so today especially if we respect the knowledge and wisdom that can be gained from life experiences. The initial incorporation of money into the traditional systems did not result in the widespread abandonment of values.

But itself money is not a bad thing and it allows a much wider range of goods and services to change hands than could ever take place otherwise. It would be very difficult for instance to exchange bead work for a plane ticket to Anchorage or to try to pay the utility bill with a bag of dry meat. Both of those items are very valuable in some communities but that value cannot be readily changed into plane maintenance or diesel fuel. When used this way to pay for things we need, money can provide support for the practice of all the values we hold dear. When new tools arrived in Native communities, people decided if they worked well or not. They kept on using those which did and discarded those which did not. Money is a tool and a good one if it is used wisely. We do not have to abandon our values to use this tool but we do need to control its behavior.

Problems arise when we stop controlling the behavior of our money and it starts to take on a life of its own. When we start valuing money for its own sake and trying to accumulate far more than we actually need, it becomes much harder to align our use of money with our Native values. We are surrounded by a wider system that helps us to allow our money to misbehave. That system encourages us to spend more than we have, and to buy all manner of things we do not really need. We are also encouraged to support development that damages our lands and waters so that we can have more money to spend. This system does not encourage sharing with others. Instead, it rewards those who accumulate lots and do not share. When acquiring more money than we need becomes a goal, even if it comes at the expense of our lands, communities, and future generations, we have gone beyond the healthy incorporation of money, and added something new to the traditional system by sanctioning uncontrolled acquisition.

When we allow organizations we are involved with to focus on wealth accumulation at the expense of everything else, we find ourselves even further removed from those traditional value systems. Now we are turning control of the money over to someone else and washing our hands of the responsibility for how it behaves. We are hoping that somehow those organizations will be held accountable, and contribute in some way to our future well-being, but we are not doing our part to control the behavior of the money very well.

Using money while staying true to our values requires that we understand the financial system, and be prepared to take control and say no to things that do not align with those values. It means understanding investing and about things like taxes and why we pay them. As communities grew in permanent locations the need for communal-use facilities increased. Schools, roads, hospitals, tribal halls, libraries, recreational facilities … all of these require much more money than a few individuals could provide so we use taxes to pay for them. None of us expect to have to shoulder the entire cost of fixing the school roof but most of us love children and are willing to pay a little towards it. We love and respect elders and do not mind contributing to programs that help them. We do that when we pay our taxes.

Public education is especially important. Private industry requires employees to have all sorts of skills but, in general, those industries expect the employees to have acquired those skills elsewhere. Imagine how expensive it would be for today’s businesses and corporations if they had to teach prospective employees to read and write! On a more personal level, think about how difficult things would be if every family had to teach all the basics to their own children with no support from the state. At least one parent would need to stay home and be a full-time teacher, assuming they had the skills to do this. The world we live in now cannot operate without public education so it makes sense that we all contribute to cover the cost and insure that we can continue to participate in the economy.

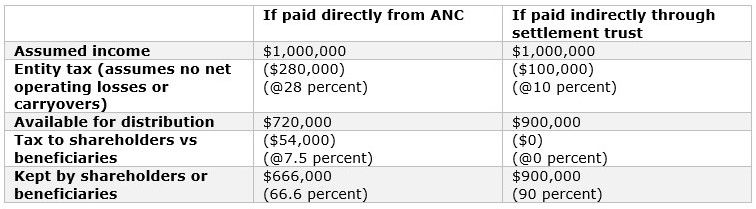

When businesses or individuals say they want to “save money on taxes’ this really means they want to spend the money on something else for their own good rather than contributing that money to the public good. It may be legal to do so but is it really fair and honest … does tax avoidance fit well with traditional values of sharing and caring about communities? What would have happened if people in subsistence-based communities had withheld labor and resources but then expected an equal share of the annual catch of salmon? When we view taxes as some kind of unfair burden rather than our way to contribute to everyone’s well-being, and find ways to avoid paying them, there will be less money for the public services we all need and use.

If too many tax payers find ways to avoid paying their share, many of the things we use will be unavailable. Almost all of the federal funding for tribal programs is derived from taxes so tribal citizens will suffer. If schools are underfunded children suffer. If we lack proper law enforcement everyone in the community suffers. If Medicare and Social Security are raided to make up for the shortfall, elders suffer. Tax cuts may sound good on paper but they are not free; we will absolutely have to pay for them. Money goes around in a circle and when we disrupt part of that circle the progress stops.

In an article on shopping locally, Jeremiah Moss suggests that we need to act like citizens rather than consumers when it comes to controlling the behavior of our money and I agree.[1] Instead of blindly following along and placing the acquisition of more money in front of everything else, we must look at the big picture. Our elders knew that if we trapped too many beaver or caught too many fish there would not be enough in the following years. If we demand more free money in the form of larger PFDs there will less to go around in the future. If wealthy people and large businesses avoid paying taxes there will be fewer services for all of us and eventually even the tax-avoiders will suffer.

At some point we all have to stop taking out and put something back in the same way as those elders preserved the animal populations by “resting’ different areas from hunting over time. Those who are taking out the most need to set an example by limiting their take and making sure their use of money is not hurting others. When we all start being more conscious about how we control our money we will have taken a step in the right direction to properly incorporate its use into our Native value systems.

[1] https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2018/10/16/17980424/shop-local-jeremiah-moss?fbclid=IwAR12FCHVDh_qQYrgS3ICwqPyPHrb_KvlNDk5mAgCfD3N71Dh6C4tDmOjtzo